1. Introduction

In his thorough investigation of migrants’ interviews with Italian Territorial Commissions for the Recognition of International Protection, Veglio (2017) illustrates that Italian case officers and interpreters often perform their professional duties in the “anthropological darkness” (Veglio, 2017: 25) while listening to migrants’ reports of their personal stories. These accounts, given by de-nationalised (ibid.) and frequently illiterate, disoriented and/or worn-out subjects, are often characterised by incomplete sections, ambiguous or inconsistent passages and, notably, a dreamlike dimension (ibid.: I), which Eurocentric professionals almost regularly fail or refuse to grasp (ibid.: 27).

Veglio (2017: 25-26) notes, for instance, that witchcraft is a widespread belief in Kenya. Prevalent in most African – and, more broadly, many non-European – cultures (Crevatin, 2018: 14), it can be understood as a search for the causes of adversities and unfathomable, unusual or abnormal events (Crevatin, 2010: 226; Veglio, 2017: 26). This belief system is reflected in the stories of many individuals who migrate to the Old Continent and explain their journeys to Italian Territorial Commissions; this is something any humanitarian interpreter ought to be aware of, as the neglect of migrants’ beliefs compromises any chance of comprehension (Veglio, 2017: 29) in an institutional context in which a certain familiarity with geopolitics and a smattering of ethnolinguistic1 concepts benefit interpreters (and case officers) to a considerable extent. In other words, interpreters (and case officers) do not always have the extensive and appropriate knowledge (ibid.: 26) needed to reconstruct the factual and emotional truth of migrants’ stories (ibid.: 1) in order to do them justice:

Abitualmente l’incarico di traduttore non viene svolto da soggetti qualificati, sia per la limitata disponibilità di competenze, sia per le anacronistiche tabelle tariffarie che regolano la liquidazione dei compensi umiliandone la dignità professionale. (Veglio, 2017: 24)

The interpreting assignment is not generally undertaken by qualified individuals, because of both the limited availability of skilled professionals and the anachronistic rates that determine payment and humiliate professional dignity.

The interpreter is supposed to be the guardian of asylum seekers’ statements (ibid.: 22) but in the end often betrays their stories by compromising their credibility, either because of gaps in cultural knowledge (ibid.: 26-27) or bias (ibid.: 18). Veglio (2017: 27) provides examples of the gradual crumbling of the credibility of migrants’ biographies, perpetrated by case officers and interpreters alike. For example, he reports the disputable rendition of the acronym MNLA (Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad, a notorious militia that is mostly made up of ethnic Tuareg fighting for the secession of Northern Mali) as “EMELELA”, a made-up lexical item whereby an interpreter failed to reproduce the content of the story told by a Malian asylum seeker.

The assessment of credibility is the hinge of any decision on international protection (ibid.: 7). In the context of asylum, “the importance of oral testimony as evidence” is paramount, “especially when, as is often the case with asylum, claimants do not possess other types of material evidence attesting to their identity and their story of prosecution” (Sorgoni, 2019: 230). Yet, while “credibility is […] explicitly linked to the facts narrated [by the asylum seeker] rather than to the individual per se” (ibid.: 231), Veglio (2017: 9) warns that the decisions issued by Italian Commissions are often based on an image of the refugee that case officers progressively construct on the basis of subjective criteria and that is partially formed in the wake of the interpreter’s output.

These acts of “institutional violence” (ibid.: 22) are frequently perpetrated because prejudice, scepticism and cynicism (ibid.: 19), coupled with insufficient knowledge of source cultures, create the preconditions for the rise of the “anthropological darkness”, which prevents case officers and interpreters from correctly assessing and translating – respectively – the migrants’ accounts of their personal vicissitudes.

Faced with this frightening institutional landscape, education appears to be the only way to try and dispel the “anthropological darkness” and foster a more accurate and appropriate approach to the rendition of migrants’ stories. To paraphrase González Rodríguez and Radicioni (2021: 385), education becomes the main key to prevent further discrimination.

When asked to play the role of the interpreter in a simulated interview with a Territorial Commission, students also experience an “anthropological darkness” that is similar to that described by Veglio, owing to their proverbial inexperience of “the things of the world” in general and their limited knowledge of geopolitical contexts (Veglio, 2017: 40) in particular. Yet, in their case, the anthropological darkness is also compounded by a deep linguistic and interactional darkness, as students are, by definition, still in the process of acquiring their relaying and coordinating skills, to use Wadensjö’s terms (1998: 108-110) for the interpreter’s translation and interaction management activities, respectively.

González Rodríguez and Radicioni (2021: 383) lay emphasis on the need for a specific training of humanitarian interpreters, one that goes beyond the didactics of linguistic and interpreting skills so as to embrace the ethical and culture-specific aspects of this sphere of public service interpreting that includes asylum interpreting (ibid.: 375). This is all the more urgent considering that the domains in which humanitarian interpreting is required are destined to increase and that the consequences of the absence or scarce quality of relevant interpreting services could be serious (ibid.: 385).

With this in mind, this paper reports on one of the role-playing methods that has been used over the past two years at the University of Trieste to design lessons for the “Introduction to English/Italian dialogue interpreting” course administered to third-year students enrolled in the BA degree programme named “Interlinguistic Communication Applied to Legal Professions”, in the Department of Legal, Language, Interpreting and Translation Studies (IUSLIT).

Broadly, this BA course combines language and legal subjects to provide students with a smattering of both before they choose an MA course2. Besides the translation of legal texts, the language courses offered include an “Introduction to English/Italian dialogue interpreting” course. On the one hand, this course enables trainees to familiarise with interpreting theory and practice, providing them with a general idea of what dialogue interpreting in specialised settings entails. On the other hand, it aims at raising awareness among those students who will eventually opt for an MA Degree in Law of the linguistic, cultural, translational, interactional and pragmatic aspects that are involved in an interpreter-mediated conversation. A specific difficulty for the teachers in designing their lessons – a difficulty that is shared by all the language trainers in the BA course – lies in the fact that they have to work and interact with students having very different levels of English proficiency. As a consequence, the lessons focus on enhancing students’ listening, condensing and reformulation abilities, as well as on emphasising the role of the interpreter as an intercultural mediator and coordinator of the conversation. The linguistic, cultural, interactional, translational and (to a limited extent) professional aspects of English/Italian dialogue interpreting are highlighted during the lessons, which revolve around practice exercises that are based on role-play simulations of dialogue interpreting situations in different institutional, legal and humanitarian contexts.

This paper focuses on the design, implementation and assessment of those role-plays that simulate migrants’ interviews with Italian Territorial Commissions. This activity is deemed relevant for the training of interpreters because, after presenting their applications for international protection in Italy, asylum seekers are “called for an interview at the Territorial Commission, the competent authority for the assessment of such applications” (Ministry of the Interior, 2020: 23) and, notably, during this interview, applicants are “interviewed in the presence of an interpreter” (ibid.). Before the lesson begins, students playing the role of the interpreter are asked for their consent to record the mock interview; the recordings that have been collected and transcribed over the past two years have provided the empirical data for this study.

The method for designing an appropriate and sufficiently authentic role-play activity is presented in Section 1. Section 2 focuses on the analysis of the transcriptions of meaningful and selected extracts of classroom interactions. It highlights the translational and interactional hurdles faced by students, and describes the characteristics of interpreting in the field of international protection. The conclusions of the study are outlined in Section 3.

2. Role-play design

2.1. Selecting the type of role-play

Role-plays are “a valuable teaching and learning tool to introduce students to the practice of dialogue interpreting” (Cirillo and Radicioni, 2017: 119). Listed among “the choices that have to be made if pedagogical resources are limited” (Ozolins, 2017: 48), they “make it possible to narrow the gap between training and real life through simulations of real-life assignments and/or the reproduction of real-life cases” (Falbo, 2020: 158).

Dwelling on the meaning of the words “role” and “play”, they analyse different aspects of this training tool. “Play” implies taking part in a performance as an “actor” who plays a given role in accordance with the “let’s pretend” principle. “Role” refers to rules and expectations characterising a given figure in society. (Falbo, 2020: 157-158)

As Ozolins points out (2017: 55), role-plays are instrumental in “securing […] understanding of ritualised linguistic encounters and their social and professional context” in the face of the chronic lack or limited availability of authentic data and teaching materials in the didactics of dialogue interpreting.

The most “traditional” type of role-play in interpreter training settings is the structured role-play (Niemants and Cirillo, 2016: 303). This type of role-play is “based on a script enacted by two instructors playing the two ‘primary parties’ in a […] negotiation and students taking it in turns to play the role of the interpreter” (Cirillo and Radicioni, 2017: 122). Interpreting students are the only ones who do not have access to the script (Niemants and Cirillo, 2016: 303), which can be either a fully-fledged, detailed script containing the turns of the primary parties in the conversation or a draft or outline illustrating the context in which the interaction takes place (ibid.); the latter type of “script” can also take the form of “an improvised unscripted dramatisation based on cards” (Falbo, 2020: 163).

Despite its potential to help students familiarise with specialised vocabulary and the translational and interactional features of dialogue interpreting (Cirillo and Radicioni, 2017: 119), “the RP [role-play] has been criticised for being inauthentic” (ibid.: 126). In particular, Stokoe (2011: 120-121) identifies two main problems related to the use of role-play as a training tool, namely “the assumption […] that plausible turns of talk can be invented on the basis of a normative understanding of how talk works” and the fact “that the interactions are simulations, in which what is at stake for participants is necessarily different from what is at stake in any ‘real’ encounter”. In order to make up for these methodological limitations, the author (2011: 125) proposes adopting “an alternative to simulated role-play” (Stokoe, 2014), namely the Conversation-Analytic Role-Play Method (CARM). Unlike traditional, structured role-plays, Stokoe’s innovative method does not depend on the “invention” of turns but makes use of authentic video-recordings of real-life interactions “as the basis for role-play and discussion” (Stokoe, 2011: 125). Although it provides the advantage of allowing users “to engage authentically, without simulation, with their everyday professional practice” (ibid.: 139), the CARM is not free from shortcomings either, as it presupposes the availability of video-recorded data (Niemants and Cirillo, 2016: 304). This precondition constitutes a challenge in many professional training fields, including the training of dialogue interpreters.

As a consequence, in spite of their unquestionable shortcomings, traditional structured role-play exercises are still widely used in the training of interpreters (Cirillo and Radicioni, 2017: 122; Falbo, 2020; Wadensjö, 2014: 437).

The preparation of the lessons for the English/Italian dialogue interpreting course addressed in the present paper relied precisely on the design of structured role-plays for a simple reason; the migrant’s interview with a Territorial Commission is (or, at least, should be) videorecorded according to the law (Ministry of the Interior, 2020: 24; Veglio, 2017: 24), but gaining access to these audiovisual materials is no easy task3. Hence, role-plays were designed without the use of authentic videorecorded interviews, though the activity was intended to “make dialogue interpreting training closer to the real world” (Falbo, 2020: 156) from the outset. This procedural imperative is also shared by Niemants and Cirillo (2016: 309) and by Cirillo and Radicioni (2017: 126), who suggest ways to make role-play activities “less artificial and more situationally and interactionally authentic” (ibid.).

2.2. Situational authenticity

During the lessons described in this paper, the Italian-speaking instructor plays the role of a President of the Territorial Commission who is in charge of asking questions to the migrant, while the English-speaking instructor pretends to be the migrant.

To shape the situational authenticity of the role-play activity, during the preliminary phase consisting in the selection and collection of materials, two sets of documents are gathered and used to draft scripts and “fill” them with plausible propositional content. As regards the structure of the interview, the design of the role-play activity relies, in general, on a series of interview protocols developed by some of the most authoritative institutions in the field of asylum, namely the EUAA (European Union Agency for Asylum) – former EASO (European Asylum Support Office) – and the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Besides the EASO Practical Guide: Qualification for International Protection (EASO/EUAA, 2018), the EASO Practical Guide: Personal Interview (EASO/EUAA, 2014)4 is regularly consulted, in that the document “promotes a structured interview method” leading “the user through the stages of preparation for the personal interview […], opening the interview and providing information […], conducting the interview […], including guidance regarding the substance of the application which needs to be explored during the interview […], and concludes with closing the interview” (EASO/EUAA, 2014). Among other guides, the UNHCR also makes available an online document entitled Intervistare i richiedenti asilo (“Interviewing Asylum Seekers”)5 to inform the appropriate preparation of case officers and assist them in asking migrants the right questions.

In particular, the Practical Guide for Asylum Seekers in Italy (Ministry of the Interior, 2020), developed on the basis of the EUAA and UNHCR guides by the National Commission for the Right to Asylum of the Ministry of the Interior, is used as the main instrument to shape the questions posed by the Italian case officer and inform the migrant’s answers. The guide is drafted in Italian (Ministero dell’Interno, 2020) and English (Ministry of the Interior, 2020) alike6, favouring the drafting of an interview that contains conversational turns by Italian and English speakers.

As regards the thematic content of the interview, the preparatory work builds on finding the transcripts of informal interviews or testimonies by migrants, which provide factual information to be included in the script. Although the widespread use of web-truths (Spotti, 2019: 74) by case officers has been shown to “hold a strong influence” and have potentially “disastrous consequences” (ibid.) on the assessment of asylum applications, in this context the web merely serves a didactic purpose, that of retrieving facts “about a country or about a language spoken in a given country” (ibid.) or about migration routes in a given country. In other words, these web-truths are not viewed as “tangible proofs of truthfulness” (ibid.) but rather as a linguistic and cultural “material” that is essential in shaping relevant role-playing activities in an interpreter training context. In particular, the information that can be found on the website ESODI/EXODI. Migratory routes from Sub-Saharan Countries to Europe7 is regularly harnessed. This website, providing material in Italian and English alike, features an interactive map of Sub-Saharan Africa and Western Europe, which the user can “explore” by clicking on given countries, cities, locations (e.g. a refugee camp) or migration routes; when the user clicks on a specific element, a window entitled “Context” pops up showing relevant information concerning the migration context of the city, location or route. For example, by clicking on the city of Agadez, a text appears, the initial excerpt of which is shown below:

The city is located in the Sahara Desert and it is the capital of the Air, one of the most traditional Tuareg Federation. Together with Al-Qatron and Sabha it is considered as a part of the “way to hell”. The northern part of Niger is considered as the meeting point for those who want to cross Sahara Desert towards Libya and Algeria. Out of the 260 migrants interviewed in Sicily, 80% stated to have contacted a smuggler to reach Libya from Agadez. In most cases, migrants got to know who to contact in Agadez simply by asking around for information about smugglers organizing trips to Libya. Indeed, as already shown in previous investigations, Agadez hosts a large number of transit houses called “Foyer”.

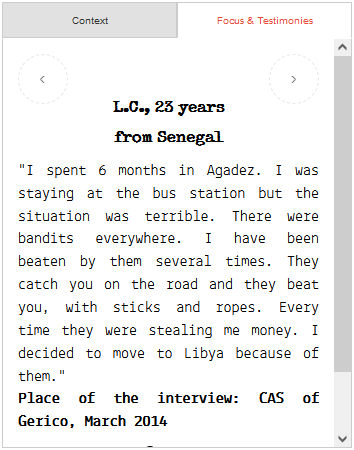

On the same webpage, a second window named “Focus and testimonies” is present, clicking on which reveals a series of excerpts drawn from interviews to migrants. The choice of the city of Agadez redirects the user to three testimonies, reporting the initials of the interviewees and the locations of the interviews. One of these testimonies is shown in Figure 1, where the acronym CAS stands for Centro di Accoglienza Straordinaria, Extraordinary Reception Centre.

A migrant’s testimony drawn from the ESODI/EXODI website, viewed on 29 September 2023.

As it provides details on migrants’ journeys and the violence that is inflicted on them, this type of information is suitable to shape an interview with a Territorial Commission, during which asylum seekers are asked to provide evidence of their “founded fear of being persecuted in their country of origin due to their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or belonging to a certain social group” and/or list the reasons why they feel they are “unable to receive protection from their country of origin” (Ministry of the Interior, 2020: 6). The Ministry of the Interior (2020: 26-27) clarifies that, according to the 1951 Geneva Convention, migrants can only be granted the status of refugee if they have “a founded fear of persecution” in their country of origin and that “examples of persecution include threats to [their] life, torture, slavery, unjust deprivation of personal freedom, female genital mutilation or serious breaches of fundamental human rights or other very serious or repeated breaches of [their] rights”. Notably, the credibility of a migrant’s story is the prerequisite for a positive assessment of his/her application for international protection (Veglio, 2017: 7), and the role of the interpreter is delicate and essential to convey this credibility to the Italian case officer.

2.3. Interactional authenticity

Regarding the interactional authenticity of the role-play activity, a few expedients are used to avoid an excessive dependence on the script, as Niemants and Cirillo (2016: 303) suggest. First, as Falbo (2020: 163) points out, “if a script is used, the players/interlocutors must not read their turns word for word, but must be as spontaneous as possible and react promptly to the interpreter’s words”. When, for instance, a student omits the translation of given lexico-phrasal items or makes a questionable translation choice, the two instructors keep pretending to be totally unfamiliar with each other’s idioms and let the interpreter-mediated conversation take the new, unexpected course determined by the student’s renditions. During one of the lessons, a student did not know the meaning of the verb to kidnap, tried to guess it from the context, rashly translated the term as rapinare (“to rob”) and “derailed” the conversation; the professors playing the role of the primary parties then pretended to understand that the migrant had been robbed rather than kidnapped, thereby contributing to rendering the three-party interaction authentic.

This is only one of the interactional expedients that the instructors resort to during the simulated interview and that Niemants and Cirillo (2016: 309) suggest adopting when designing a role-play activity that aims for a greater degree of authenticity. In this respect, the script is designed so as to reproduce the interactional dynamics that are typical of the communicative situation at work, such as the moment during the opening of the interview in which the case officer must “verify the understanding between the interpreter and the applicant” by asking “the applicant if he/she understands the interpreter and […] the interpreter if he/she understands the applicant” (EASO/EUAA, 2014: 7). This rather codified communicative exchange is included in the script to enhance the interactional (as well as the situational) authenticity of the role-play and allow students to ease into the activity.

In addition, attention is paid to reproducing the “affective displays” (Cirillo, 2012: 102) that are numerous in the conversational context of the migrant’s interview with the Territorial Commission; the fact that “interpreters’ initiatives may either promote or inhibit affective communication” (ibid.) is duly acknowledged and emphasised in class.

In this respect, the preparation of role-plays is not only informed by the above-mentioned institutional guides but also by Veglio (2017), who further illustrates the “rules of listening” (ibid.: 9) that the EUAA, the UNHCR and the Italian Ministry of the Interior have developed in their protocols based on years of experience. He reiterates that the interview with the Territorial Commission must be characterised by a comfortable and cooperative environment, a neutral and professional attitude and the will to appropriately inform migrants about their rights and duties (ibid.: 10). The collection of information from the interviewed migrant requires that the free narration be followed by a phase in which the case officer checks the truthfulness of the story (ibid.: 10) in an empathic and encouraging way (ibid.: 11). Moreover, the case officer ought to opt for simple, generally open and non-leading questions, favouring dialogue and clarification (ibid.: 10). Indeed, rigid sets of predetermined questions should give way to a logical and flexible sequence, one that adapts to the migrant’s narration (ibid.: 28).

The case officer is also required not to interrupt the interpreter or the migrant during his/her narration (ibid.: 10), and to be empathic and encouraging. This is, at least, what “theory” suggests, whereas Veglio (2017) notes that Italian case officers and interpreters often jeopardise dialogue and cooperation, “reading” asylum applications through their own cultural filter (ibid.: 25). Case officers frequently prefer “suffocating” the introductory part of the interview with close questions – such as asking for dates, names and numbers –, which stifle any chance for dialogue from the start (ibid.: 28). Indeed, Veglio’s (2017) analysis of interview minutes reveals a typically Western (Crevatin, 2010) tendency for classification stemming from the European doctrine of measurability (Veglio, 2017: 29).

2.4. Limitations of the method

However functional to promoting “the acquisition of knowledge and skills enabling the interpreter to manage interaction” (Falbo, 2020: 157) in the specific institutional context of international protection in Italy, this role-play design method presents at least a couple of limitations. First, as Veglio (2017: 25) notes, migrants’ turns are in most cases characterised by hybrid, impure and corrupt vocabulary. Their linguistic repertoire frequently includes pidgins and creoles8 (ibid.: 25) and can often be categorised as “rotten English”, i.e. a mix of an English-based pidgin, ungrammatical English and good English, that is sometimes enriched with idiomatic expressions (ibid.); this language is disorderly and creates disorder (ibid.). Yet, the script-based interactions that are proposed to students of the BA course in Interlinguistic Communication Applied to Legal Professions comprise, besides turns in Italian, turns in standard – however simple – English, i.e. the “type of English [that] has undergone standardization, which means that it has been subjected to a process through which it has been selected, codified and stabilized, in a way that other varieties have not” (Trudgill and Hannah, 2013: 1). The choice of this variety stems from the fact that it is the one that Italian students are most familiar with and, especially, from the need not to excessively divert their attention from the acquisition of interactional skills by means of a significantly disorderly conversation; notably, at this stage of their learning path, the BA students in question have attended language courses but have never received any previous training in dialogue interpreting and, therefore, need a step-by-step method at the very outset of their journey into the world of interpreting (whether this journey ends up to be long or not).

The second limitation lies in the fact that this type of role-play is made up of structurally different turns, namely rather short Italian turns (the case officer’s questions) and rather long English turns (the migrant’s narration of events); these types of turns constitute the prototypical adjacency pair (Sacks et al., 1974: 716) of the personal interview for international protection. While drafting the scripts, an effort is regularly made to avoid rapid-fire successions of questions, which downgrade the conversation with the migrant to a police interview (Veglio, 2017: 25). Indeed, Veglio (2017: 11) insists on the need for the case officer and the interpreter to create an atmosphere of trust in order to reach, together with the applicant, the institutional goal of gathering reliable information on his/her journey and situation. Hence, the turns of the Italian speaker reflect this underlying need to arrange an accommodating conversation. Regarding English turns, they are devised to be less confused, unchronological and incomplete than Veglio (2017: I) suggests they are in practice, with the purpose of giving rise to rather dense sequences of talk, which the student will gradually learn to manage by carrying out explicit coordination strategies such as asking for clarifications, inviting interlocutors to start or continue talking and interrupting them (Merlini, 2015: 105). As regards interruptions, however, the trainees are informed that, in the specific context of asylum applications, the migrant is provided with “an opportunity to give an uninterrupted personal account of the reasons for applying for protection” (EASO/EUAA, 2014: 11) and the interpreter is, therefore, called upon not to interfere with the free narrative. Incidentally, although professional interpreters can and often do manage long turns by taking notes (Cirillo and Radicioni, 2017: 133), the students are invited not to do so – with the exception of names, numbers, enumerations and other “problem triggers” (Gile, 1995: 171) –, because they have not yet been trained in consecutive interpreting and have received no note-taking instruction at this stage of their university career. As clarified in the Introduction to this paper, this course is named “Introduction to English/Italian dialogue interpreting” precisely because it is the students’ initial encounter with the interpreting activity, a course that provides the first opportunity to challenge their abilities to express themselves orally, harness their short-term memory and acquire interactional skills.

Despite this second limitation, the method and the expedients described enable the creation of role-plays that feature “difficult turns”, i.e. turns that offer comprehension difficulties because they are either too short or too long (Baraldi, 2018). While the former challenge the students’ ability to rapidly and correctly translate questions – the morphosyntax of which varies considerably from Italian to English –, the latter test their listening and comprehension skills, inducing them to learn, internalise and adopt those strategies that enable them not only to translate but also “to manage interaction dynamics” (Falbo, 2020: 159) and “to develop skills and decision-making abilities” (ibid.: 160). In this respect, these fundamentally different but complementary turns appear to be “moderately difficult”, or appropriate for third-year Italian students at their first encounter with English/Italian dialogue interpreting.

3. Simulating the interview with the Territorial Commission

The present Section illustrates the analysis of selected excerpts drawn from the transcriptions of the recordings of the simulations carried out in class; the recordings are listed in Table 1. All the recordings refer to two role-playing activities that were used with different groups of students over the last two years; the role-plays simulate two interviews with two fictional characters, a Nigerian and an Eritrean migrant named John Udu and Harry Tekle, respectively. Owing to their length, each simulated interview was divided into three parts which were interpreted by three different students; each recording, thus, represents the performance of one student and the interpretation of one portion of an interview, rather than one single interview in its entirety.

Table 1. Recordings analysed.

| Recording 1 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 1) |

| Recording 2 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 2) |

| Recording 3 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 3) |

| Recording 4 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 1) |

| Recording 5 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 2) |

| Recording 6 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2022 (part 3) |

| Recording 7 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 1) |

| Recording 8 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 2) |

| Recording 9 | John Udu’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 3) |

| Recording 10 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 1) |

| Recording 11 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 2) |

| Recording 12 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023 (part 3) |

| Recording 13 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023bis (part 1) |

| Recording 14 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023bis (part 2) |

| Recording 15 | Harry Tekle’s interview with the Territorial Commission 2023bis (part 3) |

Before starting the simulation of the interview, students were duly informed about the context of situation and, especially, the role of the interpreter therein. This information was and can be found in the above-mentioned guides about international protection applications. The EUAA (2014), for instance, emphasises that, at the beginning of the interview, the case officer must make sure that the interpreter and the migrant understand each other. The transcription of one of these introductory interactions, drawn from recording 7, is shown in Example (1), where CO indicates a turn uttered by the case officer, S introduces a student’s turns and the letter M anticipates the migrant’s turns.

(1)

| 1 | CO | [addressing S] per favore dica al signor Udu che io mi chiamo Marco Ubaldi sono il presidente della Commissione Territoriale che deciderà sulla sua domanda di protezione internazionale (.)a poi si presenti anche lei dica di essere l’interprete [please tell Mr Udu that my name is Marco Ubaldi I am the President of the Territorial Commission who will decide on his application for international protection (.) then introduce yourself too please tell him that you are the interpreter] |

| 2 | S | good morning Mr Udu this is Marco Ubaldi he is the President of the Territorial Commission who will decide on your (.) application for the visa actually (.) and I am XXX I will be your interpreter today |

| 3 | M | good morning thank you |

| 4 | S | grazie buongiorno [thank you good morning] |

| 5 | CO | signor Udu capisce cosa dice l’interprete [Mr Udu do you understand what the interpreter says] |

| 6 | S | do you understand everything I say |

| 7 | M | yes I do |

| 8 | CO | e lei capisce tutto quello che dice il signor Udu [and do you understand everything that Mr Udu says] |

| 9 | S | sì capisco tutto [yes I understand everything] |

| a. The symbol (.) indicates a pause, while XXX replaces students’ names. | ||

In turn 2, the student’s choice of translating the noun phrase domanda di protezione internazionale (“application for international protection”) as application for the visa suggests that the information about specialised lexicon provided in the briefing phase had not been internalised yet; the student’s hesitation was also signalled by a pause and the addition of the hedge actually. Incidentally, while interpreted speeches have been found to contain fewer hedges than original speeches (Magnifico and Defrancq, 2017; Fu and Wang, 2022), the recordings analysed point to a tendency to add hedges, which can be interpreted as an indication that the trainees are still grappling with the development of their relaying and coordination skills.

As regards interactional moves, turns from 5 to 9 illustrated when the case officer makes sure that S and M understand each other, and showed that S coordinates the interaction smoothly by producing translational and conversational turns alike, depending on whether CO’s question is addressed to M or to S him/herself. In particular, 6 suggests that the student coordinated the talk and negotiated the asymmetric relation between the primary participants appropriately, asking the “migrant” a direct and concise question that promotes an empathic communicative exchange. Yet the recordings analysed showed that trainees still need to improve in these areas.

(2)

| 14 | CO | signor Udu sa perché è qui oggi [Mr Udu do you know why you are here today] |

| 15 | S | do you know why are you here today |

(3)

| 9 | CO | allora signor Tekle sa perché è qui oggi [so Mr Tekle do you know why you are here today] |

| 10 | S | we would like to know if you know why you are here |

In Example (2), drawn from recording 1, turns 14 and 15 showed that S uttered a concise but syntactically intricate turn, standing out for the presence of an embedded question that was incorrectly asked with an inversion between the pronoun you and the verb form are. In Example (3) from recording 10, instead, turn 10 displayed a more correct but redundant, verbose and inefficient translation of the question in 9, which was likely to jeopardise clarity and, in addition, did not reproduce the pragmatic force of CO’s question. Incidentally, in the debriefing phase of the role-play activity, students generally confessed to being aware of their mistakes and, in general, the rules of English grammar and syntax, but the correct application of the latter is often a difficult task while starting to learn how to interpret.

Example (4), extracted from recording 10, shows the simulation of the stage in the interview where the migrant was informed that the minutes of the videorecorded conversation would later be signed exclusively by the interviewer and the interpreter: only if the migrant specifies anything or the interview is not filmed owing to an explicit and motivated request by the migrant will the migrant be asked to sign the minutes, too (Ministry of the Interior, 2020: 24).

(4)

| 30 | CO | alla fine del colloquio io e l’interprete firmeremo il verbale (.) a lei sarà richiesto di firmarlo solo se avrà fatto delle precisazioni o richiesto delle correzioni [at the end of the interview the interpreter and I will sign the minutes (.) you will only be requested to sign if you have specified anything or requested that the minutes are corrected] |

| 31 | S | we are going to sign the minutes |

S’s turn was notable for the controversial choice of the pronoun we. This added ambiguity, as it did not clarify the identities of those who, within the triadic exchange, would ultimately sign the minutes of the meeting. In addition, the omission of the following part of CO’s turn made the instructions to follow difficult to understand. This is evidence of the kind of “interactional darkness” in which inexperienced interpreters often operate.

In particular, the analysis of the students’ turns revealed, at times, a certain inaccuracy in translating affective displays, in line with Cirillo’s (2012) discoveries. The present study on the interpretation of migrants’ interviews with Territorial Commissions adopts “a broad working definition of affect, which includes expressed feelings, attitudes, and relational orientations of all kinds” (ibid.: 103):

General as it may be, this definition highlights the methodological perspective of this study, which explores not so much speakers’ inner states, but the ways in which these are displayed, and how such displays are negotiated and oriented to by speakers themselves. In other words, and in line with an interpersonal social perspective, the main concern is with how affect is made relevant by co-participants throughout the interaction.

As Cirillo (2012: 106) specifies, “affective displays are far from absent in institutional interactions” and this holds true for the discursive sphere of international protection and, hence, the field of humanitarian interpreting. Take the following excerpt taken from recording 3:

(5)

| 18 | CO | se la sente di raccontarci come andò avanti il suo viaggio [do you feel like telling us how your journey continued] |

| 19 | S | can you tell us how your journey continued |

Turn 18 was the core of an “affective sequence” (ibid.: 113) that saw the President of the Territorial Commission living up to his/her responsibility to develop “a good communication atmosphere, in which all relevant persons feel safe and interact in a positive manner […] to create such an atmosphere of trust and confidence” (EASO/EUAA, 2014: 6)10. By asking the migrant if s/he felt like carrying on the narration of the journey that brought him/her to Italy, CO tried to discursively hide the inherent asymmetry between their roles (Veglio, 2017: 10) and take on an encouraging attitude that excludes any abuse of power, biased comment or allusion (ibid.: 11). The student’s choice to translate se la sente with can you deprived the case officer’s question of its affective dimension, adding the ambiguity of the modal can to the query and making it sound like Are you able to tell your story? or Are you entitled to tell your story? In this respect, S’s turn qualified as a “non-close rendition” (Dal Fovo and Falbo, 2021) in that it departed from the corresponding primary speaker’s turn and set forth something different. Thus, what ought to be “a three-party affective sequence” (Cirillo, 2012: 113) ended up being an untranslated affective display that has the potential to hamper empathic communication.

Instances of inhibition of affective communication could be frequently observed in the analysis of the transcriptions of students’ turns, not only when the shorter Italian turns were translated into English but also and especially when the longer English turns illustrating the heart-wrenching journeys and adventures of migrants were rendered into Italian. Example (6) shows the three different renditions (drawn from recordings 6, 12 and 15) of a single turn (exemplified by the one extracted from recording 6 and shown in the first line) proposed by three different students11, who translated the answer to the question Com’era la vita nel campo profughi di Shagarab? (“What was your life like in the Shagarab refugee camp?”).

(6)

| 28 | M | the conditions of life were dramatic (.) it’s a hellish place (.) there were more than sixteen thousand people (.) food and clothes were not enough you were not allowed to work and you were not safe because the Rashaida entered and kidnapped people (.) if I think of that place I go crazy |

| 29 | S(1) | dice le condizioni di vita erano drammatiche (.) c’erano più di sedicimila persone il cibo e i vestiti non erano sufficienti (.) non erano sicuri perché spesso i membri della tribù Rashaida arrivavano e rapivano le persone (.) si sente un po’ traumatizzato [he says that the conditions of life were dramatic (.) there were more than sixteen thousand people food and clothes were not enough (.) they were not safe because the Rashaida often arrived and kidnapped people (.) he feels a bit traumatised] |

| 29bis | S(2) | le condizioni di vita erano abbastanza drammatiche (.) c’erano più di sedicimila persone (.) non c’era abbastanza cibo e non c’erano vestiti (.) non potevo lavorare e ogni tanto arrivavano i Rashaida e rapivano le persone (.) quando penso a quel posto divento nervoso (.) non ci penso [the conditions of life were rather dramatic (.) there were more than sixteen thousand people (.) food was not enough and there were no clothes (.) I was not allowed to work and sometimes the Rashaida arrived and kidnapped people (.) when I think of that place I become nervous (.) I don’t think about it] |

| 31 | S(3) | le condizioni erano drammatiche (.) eravamo in sessantamila (.) non si poteva lavorare non eravamo al sicuro anche perché i Rashaida rapivano alcuni di noi (.) non mi sento molto bene quando ripenso a quell’esperienza era un posto molto sporco [the conditions were dramatic (.) we were sixty thousand people (.) you were not allowed to work we were not safe also because the Rashaida used to kidnap some of us (.) I don’t feel very well when I think back on that experience it was a very dirty place] |

One of the most obvious elements in the recordings shown in Example (6) was the systematic zero-rendition (Wadensjö, 1998: 108) of the evocative phrase it’s a hellish place. Besides the observation of further omissions (e.g. that of food and clothes were not enough in 31) and incorrect renditions (e.g. sixteen thousand turning into sixty thousand in 31), the translations of the final, pragmatically significant sentence if I think of that place I go crazy stuck out. While S(1) reformulated it into I feel a bit traumatised, S(2) mitigated the illocutionary force of the utterance describing the migrant’s state as nervous rather than crazy; s/he also translated if I think about it as I don’t think about it, which is enough to qualify his/her turn as a non-close rendition. The turn by S(3), instead, appeared to be an expanded rendition (Wadensjö, 1998: 107) characterising Shagarab’s camp with an additional and made-up (however plausible) feature, that of being a very dirty place. Like 29 and 29bis by S(1) and S(2), however, 31 by S(3) also saw a mitigation of the pragmatic value of the sentence if I think of that place I go crazy, whose translation gave back the picture of a refugee who does not feel very well.

In general, the examination of the data suggests that most students seemed to struggle with the translation of negativity, as shown by S(2)’s rendition of dramatic as rather dramatic. This tendency was further suggested in the turns that are displayed in Example (7) and were drawn from recording 5:

(7)

| 9 | CO | le è successo qualcosa di spiacevole durante il suo viaggio verso il Sudan [did something unpleasant happen to you during your journey to Sudan] |

| 10 | S | did something happen during your journey to Sudan |

| 11 | M | yes a lot of bad things |

| 12 | S | sono successi degli inconvenienti [some problems occurred] |

In a nutshell, the analysis indicates that most students acted as if they struggled to, refused to or refrained from conveying negative descriptions of events. These tendencies were especially evident in the translation of longer narrative turns, where the trainees’ difficulties in understanding the geopolitical context of the story stood out. In this regard, the students not only faced an “interactional darkness” but also previewed the “anthropological darkness” that Veglio (2017: 25) denounces in his analysis of how interviews with Territorial Commissions are conducted and interpreted in Italy.

(8)

| 5 | CO | le va di raccontarci le vicende che l’hanno portata fino a qui [do you feel like telling us the events that have led you here] |

| 6 | S | could you tell us the story that led you to come here |

| 7 | M | yes (.) one day five years ago I was with my father on our way back to Benin City (.) some people with masks stopped our vehicle and asked me to get out (.) they tied me up while they shot at my father (.) just in front of me (.) I was eager to save my dad but those people put me inside the car covered my face and brought me in the bush (.) I was shocked (.) I didn’t even know if my father had survived |

| 8 | S | praticamente (.) cinque anni fa [basically (.) five years ago] (.) [addressing M] excuse me where were you going (.) you and your father |

| 9 | M | we were going back home to Benin City |

| 10 | S | thank you (.) io e mio padre stavamo tornando a casa a Benin City e a un certo punto una macchina al cui interno c’erano persone con delle maschere ci ha fermati (.) hanno sparato a mio papà proprio di fronte a me ma io non potevo fare niente (.) mi hanno messo una maschera e: (.) mi hanno portato in un cespuglio [my father and I were going back home to Benin City and suddenly a car in which there were some people with masks stopped us (.) they shot at my father just in front of me but I couldn’t do anything (.) they put a mask on my face and: (.) they brought me in a shrub] |

The interaction illustrated in Example (8) and taken from recording 8 indicates that the student in question (and, in general, most students) still grappled with the appropriate adoption of interactional strategies such as interrupting interlocutors to divide long turns into smaller chunks or asking for clarifications, which would favour the comprehension and rendition of M’s turns. In fact, in turn 8, S asked M to repeat his destination and his father’s, which led to a more accurate translation. Yet, only one detail of M’s story was preserved thanks to S’s request for clarification, unlike many others that were omitted. Indeed, zero-renditions of given phrases and sentences uttered by the migrant were also evident here, such as the omissions of our vehicle, [they] asked me to get out, they tied me up and I was shocked. Broadly, generalisations appeared to be the norm in the trainees’ interpretations of migrants’ stories, whose Italian counterparts often sounded like reduced renditions (Wadensjö, 1998: 108) of the original accounts. An example of generalisation could also be observed in recording 3, where the asylum seeker’s sentence As soon as you reach Libya, you are in a big prison turned into Nel momento in cui arrivi sei in una prigione (“As soon as you arrive, you are in prison”).

Besides these findings, turns 5 and 6 showed that the translation of affective displays remains problematic at an early stage of the learning path (le va translated as could you). Furthermore, the typically Italian hedge praticamente (literally “practically” but meaning “basically”, “essentially” when used as a hedge) showed up in 8, suggesting that hedging strategies are adopted to make up for a lack of comprehension of the English-speaking interlocutor’s turn. And notably, turn 10 provided an example of the linguistic, interactional and anthropological darkness that students are generally immersed in. M revealed that those people […] brought me in the bush; after a few hesitations, the student reported that the migrant was portato in un cespuglio. The Italian term cespuglio only corresponds to one of the meanings of the polysemous English term bush, that denoting “a low densely branched shrub”12, “a large plant which is smaller than a tree and has a lot of branches”13 or “a plant with many small branches growing either directly from the ground or from a hard stem, giving the plant a rounded shape”14. If, rather than randomly selecting one meaning (or the only one of which s/he is aware of), the student had asked for a clarification of the contextual meaning of the term bush, s/he would have learnt that “(especially in Australia and Africa) [a bush indicates] an area of land covered with bushes and trees that has never been used for growing crops and where there are very few people”15. This simple and rapid request for clarification would have dispelled all his/her doubts as to how an individual could ever be “brought in a shrub”.

The same comments apply to S’s translation of the sentence displayed in turn 3 in Example (9), which is drawn from recording 9:

(9)

| 3 | M | we were almost three hundred people in a small hut |

| 4 | S | eravamo circa trecento persone (.) in una struttura che non si può neanche considerare una casa [we were almost three hundred people (.) in a building that cannot even be considered a house] |

While the translation of hut as a structure that cannot even be considered a house indicated a certain ability to reformulate, turn 4 also demonstrated students’ “dangerous” tendency not to ask for clarification when they do not understand something.

The students’ difficulties in understanding migrants’ stories owing to their limited extralinguistic knowledge became manifest in many excerpts of the transcribed interactions, sometimes even when specific cultural and/or geopolitical aspects of the migrant’s country of origin had been illustrated ahead of the simulation, during the briefing phase of the role-play activity. The following are examples of selected interactions taken from recordings 2 and 11, respectively. The references to the terrorist group Boko Haram and Rashaida tribesmen were explained by the instructors before the role-play activities began.

(10)

| 13 | CO | come fa a sapere che si trattava proprio di soldati del gruppo armato Boko Haram [how do you know that they were precisely soldiers of the Boko Haram armed group] |

| 14 | S | how do you know that they were a terrorist group |

| 15 | M | at that moment I was afraid and I suspected they were Boko Haram soldiers but I realised it only later (.) when I arrived in the bush they uncovered my eyes and I saw hundreds of people detained including women and children (.) they told me that as a young boy I had to join Boko Haram |

| 16 | S | praticamente lo sapeva ma l’ha capito bene dopo un po’ (.) quando gli hanno scoperto il viso e lui ha visto che c’erano tanti prigionieri (.) anche bambini (.) gli hanno chiesto di unirsi a Boko Haram [basically he knew that but he realised it for sure after a while (.) when they uncovered his eyes and he saw that there were a lot of people detained (.) even children (.) they asked him to join Boko Haram] |

(11)

| 21 | M | during the crossing I was kidnapped by Rashaida tribesmen |

| 22 | S | nel confine sono stato rapito dalle forze dell’ordine del Sudan [in the bordera I was kidnapped by the law enforcement agents of Sudan] |

| 23 | CO | erano in uniforme [were they wearing a uniform] |

| 24 | S | were they wearing a uniform |

| 25 | M | no (.) they were Rashaida tribesmen they were not in uniform |

| 26 | S | no ho sbagliato erano dei russi [no I made a mistake they were Russians] |

| 27 | CO | e cosa ci facevano i russi in Sudan [and what were Russians doing in Sudan] |

| 28 | S | (addressing CO) mi scusi chiedo un chiarimento [sorry I am going to ask for clarification] (addressing M) sorry who were they |

| 29 | M | the Rashaida tribesmen an ethnic group living in Eritrea and Sudan (.) they kidnap people |

| 30 | S | (addressing M) ah ok I’m sorry for this misunderstanding (addressing CO) mi scuso è stato un errore mio si trattava dei membri della tribù Rashaida [I apologise it was my mistake they were Rashaida tribesmen] |

| a. The phrase “in the border” is an attempt at reproducing the incorrect Italian “nel confine” standing out in S’s turn. | ||

The first of the two interactions, displayed in Example (10), showed that S refrained from calling Boko Haram by its name. The fact that the nature of the armed group had not been internalised, grasped or listened to by the trainee during the briefing was further attested in turns 15 and 16, where s/he selected one of the least appropriate verbs (gli hanno chiesto di, “they asked him to”) to convey the threatening manners of Boko Haram soldiers who, in turn 15, force the migrant to join the terrorist group but become much kinder in turn 16, where they are described as people who invite others to join their gang.

Example (11) indicates the hurdles faced by another student while trying to grasp who Rashaida tribesmen were. They were first transformed to Sudanese law enforcement agents (forze dell’ordine del Sudan) and later to indistinct Russians (dei russi). Incidentally, Example (11) shows that, during the dialogue interpreting lessons, the instructors are always ready to steer the conversation or, rather, let themselves be dragged into the conversation that the students co-construct; in other words, they are used to going off script to simulate a natural conversation and to make the interaction sound as authentic as possible. Moreover, this second interaction also demonstrates that, however destabilising and inadvisable “creative” renditions may be, an interpreter should never give in, as a professional interaction can always be brought back “on track” by continuing to ask the primary speakers for clarification and, especially, by taking responsibility, apologising (I’m sorry for this misunderstanding; mi scuso è stato un errore mio in turn 30), smiling and trying to create a relaxed atmosphere in which parties can trust each other.

More broadly, as anticipated in the introductory section of the paper, the examples in this Section suggest that working in the translational, interactional and anthropological darkness is bound to compound comprehension and jeopardise migrants’ efforts to obtain asylum. Even if they are performed in a training setting, the role-plays described above show how easy it is not to do justice to the vivid stories of these individuals who want and demand that their words be translated “impartially” and “literally” (Ministry of the Interior, 2020: 24) with a view to obtaining asylum.

4. Conclusions

The “Introduction to English/Italian Dialogue Interpreting” course offered at the University of Trieste within the BA degree programme named “Interlinguistic Communication Applied to Legal Professions” broadly aims at familiarising students with the linguistic, cultural, translational, interactional and pragmatic aspects that are at stake in a series of professional contexts in which the interaction is mediated by a dialogue interpreter.

Among the activities proposed within this course, structured role-plays are designed to simulate migrants’ interviews with Italian Territorial Commissions, namely a communicative context in which the presence of an interpreter is regularly required. The situational and interactional authenticity of role-play activities is enhanced by consulting institutional documents by the EUAA, the UNHCR and the Italian Ministry of the Interior, by drawing factual information from selected testimonies by migrants, by extrapolating further factual and interactional cues from Veglio’s (2017) examination of how asylum seekers’ personal stories are assessed and interpreted in Italy and by grounding role-play activities on a dialogic and conversation-analytic approach.

Broadly, students’ difficulties in managing the triadic exchange seem to reflect the difficulties that, according to Veglio (2017), both case officers and (frequently non-professional) interpreters encounter in the real world, while assessing and interpreting migrants’ stories. The interactions recorded in the training setting showed that the students’ turns were characterised by the presence of hedges, instances of inhibition of affective communication and a generalised tendency not to resort to coordination strategies such as asking for clarification, inviting interlocutors to start or continue talking and interrupting them, which play a crucial role in dialogue interpreting (Merlini, 2015: 105).

The alternation between relatively short, direct questions asked in Italian and comparatively long, narrative answers in English confirms that the interpreters – whether professionals or students – who take part in the triadic exchange unfolding during the interview with the Territorial Commission embark on a “rhythmic quest” (Veglio, 2017: 22), because futile efforts to store information without coordinating the interview will lead to a loss of information, while frequent interruptions are bound to fragment the narrative and jeopardise the fluidity, persuasiveness and credibility of the migrant’s story (ibid.).

However discouraging, this interpreting landscape only has serious consequences in professional contexts. In the classroom, the objective to inform students of the risks of perpetrating acts of “institutional violence” (ibid.) during a migrant’s interview with a Territorial Commission is subordinate to a broad training objective, that of accustoming them to swiftly and concisely translating short turns, producing English sentences that are grammatically and syntactically correct, managing long turns by adopting appropriate coordination strategies, and reproducing affective displays by avoiding zero- and non-close renditions, with a view to gradually dispell the linguistic, interactional and anthropological darkness that is the frequent prerequisite of discrimination in the context of international protection.