Introduction

Alors que l’intégration de l’intelligence artificielle a transformé le paysage de l’enseignement supérieur au cours de la dernière décennie (Grassini, 2023), les nouvelles technologies dans les contextes académiques suscitent souvent des perceptions négatives et des inquiétudes (Ismatullaev et Kim, 2024). Comme le montrent les prises de position échangées au sein des espaces de discussion de l’enseignement supérieur et relayées dans les médias généralistes après la commercialisation de GPT-3 en novembre 2022, l’arrivée de l’IA générative (IAGén) dans l’enseignement supérieur ne fait pas exception. Les préoccupations soulevées par le corps enseignant portaient notamment sur l’absence de bénéfices liés à l’usage de l’IAGén, les risques de tricherie et de plagiat, le manque d’expérience des enseignants dans son utilisation à des fins pédagogiques, ainsi que les difficultés pratiques anticipées (Iqbal et al., 2022). Bien que l’étude rapportée par Iqbal ait été menée peu après la sortie de GPT-3, ces thématiques et attitudes sont restées relativement constantes, comme le montrent d’autres études publiées depuis.

Plusieurs études ont montré que ces attitudes négatives sont souvent liées à la crainte du plagiat et de la tricherie (Nguyen, 2023), l’une des préoccupations les plus fréquemment exprimées. Cette inquiétude se justifie par le fait que les modèles de langage sont entraînés sur de vastes corpus de données préexistantes, lesquelles peuvent réapparaître dans les textes générés, sous une forme difficile à détecter sans outils spécifiques (Khalil et Er, 2023). Si un débat persiste quant à savoir si l’usage de l’IAGén constitue ou non une forme de plagiat, son emploi pour rédiger des textes entiers est, dans la majorité des contextes académiques, assimilé à de la tricherie.

Une autre source de réticence envers l’IAGén vient de la conception selon laquelle son utilisation empêcherait la pensée critique et l’effort cognitif des apprenants (Gandhi et al., 2023), et du fait qu’une dépendance excessive à l’IAGén serait par conséquent néfaste à l’apprentissage. Afin de se préparer à l’accroissement probable de la présence d’outils d’IA dans l’éducation et d’éviter qu’ils ne deviennent un frein à la pensée critique, plusieurs études se sont concentrées sur l’adaptation de leur usage dans le but d’en faire des facteurs de développement (voir Dergaa et al., 2023 ; Qawqzeh, 2024 ; Wu, 2024).

En parallèle, des études sur les perceptions des enseignants et des étudiants ont mis en évidence les avantages potentiels de l’IAGén, notamment sa capacité à raccourcir et faciliter certaines tâches (Lee et Perrett, 2022), à générer des retours personnalisés (Kim et Kim, 2022), ou encore à offrir un accès rapide à l’information, ce qui peut aider les étudiants à fluidifier leur processus d’écriture (Iqbal et al., 2022) et à développer une vision d’ensemble plus claire lors leurs recherches documentaires (Darwin et al., 2024). Ces possibilités, parmi lesquelles la génération automatique de texte ou la traduction, ont été largement explorées dans la littérature sur les modèles de langage génératifs (Guo et Lee, 2023 ; Gao et al., 2023 ; Huang et Tan, 2023 ; Imran et Almusharraf, 2023).

Indépendamment de la question des avantages et des limites de l’IAGén, il est d’abord essentiel d’examiner les attitudes à son égard à l’université, dans la mesure où celles-ci peuvent influencer son intégration dans les Writing Centers, centres d’accompagnement à l’écriture universitaire, généralement animés par des tuteurs formés pour aider les étudiants à développer leurs compétences rédactionnelles. Concernant les différences de perception entre étudiants et enseignants, plusieurs études ont montré que ces derniers adoptent une posture plus stricte et prudente vis-à-vis de l’IA que les étudiants, et qu’ils déclarent plus fréquemment qu’elle nuit à l’apprentissage ou qu’elle devrait être totalement bannie de l’enseignement (Ma, 2023). Cette divergence pourrait s’expliquer, entre autres, par un écart d’usage et de familiarité avec les outils d’IA. Si les étudiants sont des utilisateurs plutôt réguliers de l’IA (Schiel et Bobek, 2023), les enseignants déclarent des fréquences d’utilisation plus faibles et des compétences plus limitées (Chounta et al., 2022 ; Dilzhan, 2024). Or, une pratique moins régulière et un niveau de maîtrise plus faible sont des facteurs susceptibles de freiner l’acceptation de ces outils (Galindo-Domínguez et al., 2024).

La recherche présentée dans ce chapitre s’intéresse à la croissance anticipée de l’usage des outils d’intelligence artificielle dans l’enseignement supérieur. Dans ce contexte, comprendre les attitudes des étudiants et des enseignants apparaît comme un préalable essentiel pour accompagner cette évolution. Au Graduate School Writing Center de l’Université Clermont Auvergne, les tuteurs ont observé une grande diversité de réactions face aux outils d’IAGén : certains refusaient catégoriquement leur usage pendant les séances, tandis que d’autres se montraient hésitants, exprimant des inquiétudes liées au plagiat, des doutes quant à la qualité des textes générés, ou évoquant des consignes restrictives de la part de leurs enseignants. Ces réticences ont complexifié l’intégration de méthodes pédagogiques fondées sur l’usage de l’IAGén dans les séances de tutorat.

Pour analyser ces préoccupations, nous avons mené une étude auprès des étudiants fréquentant notre Writing Center ainsi que de leurs enseignants. Celle-ci vise à répondre aux questions de recherche suivantes :

• Quelles sont les principales préoccupations des enseignants et des étudiants concernant l’usage de l’IAGén dans l’apprentissage et dans les tâches d’écriture universitaire ?

• Comment les perceptions négatives de l’IAGén influencent-elles la volonté des étudiants de recourir à ces outils dans leur processus d’écriture ?

Apporter des éléments de réponse à ces questions nous semble essentiel pour définir, sur une base empirique, des principes d’intégration de l’IAGén dans les Writing Centers, et pour accompagner les étudiants dans le développement de compétences clés en écriture universitaire. Dans notre discussion, nous proposerons des pistes pour atténuer les perceptions et préoccupations négatives des enseignants et des étudiants vis-à-vis de l’IAGén, et nous formulerons des recommandations pédagogiques à destination des tuteurs, afin de les aider à mobiliser l’IAGén de manière pertinente en séance et à promouvoir des pratiques responsables dans le cadre de l’écriture universitaire.

Méthode

En juin 2024, 173 étudiants de niveau Master inscrits au Graduate School Writing Center à l’UCA ainsi que seize enseignants ont été contactés par courriel. Trente-deux étudiants et dix enseignants ont accepté de participer à notre étude. Pour évaluer l’usage et la perception de l’IAGén dans chaque groupe, deux questionnaires distincts ont été élaborés, en s’inspirant des travaux de Zablot et al. (2025) et de Demonceaux et al. (2025). Ces questionnaires portaient sur l’utilisation de l’IAGén en contexte universitaire : fréquence d’usage, niveau de compétence perçu et impact de l’IAGén sur les activités universitaires. Une autre section explorait les opinions des participants sur l’IAGén dans l’enseignement supérieur : avis sur son interdiction éventuelle, perception des risques associés à son usage et représentations des attitudes d’autres étudiants ou enseignants à son égard. Toutes les réponses ont été recueillies de manière anonyme. En complément, nous avons mené de courts entretiens semi-directifs avec deux tuteurs du Writing Center afin de recueillir leur retour d’expérience sur les réactions des étudiants face à l’usage de l’IAGén durant les séances de tutorat.

Résultats

En ce qui concerne l’utilisation des technologies alimentées par l’IAGén, les réponses des étudiants révèlent que seuls trois d’entre eux, sur trente-deux, n’avaient jamais utilisé d’outil d’IAGén. À l’inverse, seuls trois des dix enseignants déclaraient en avoir fait usage dans le cadre de leurs activités universitaires. Les principales réticences exprimées par les enseignants concernaient la fiabilité des contenus générés ainsi qu’un manque de compréhension quant à la finalité de ces outils.

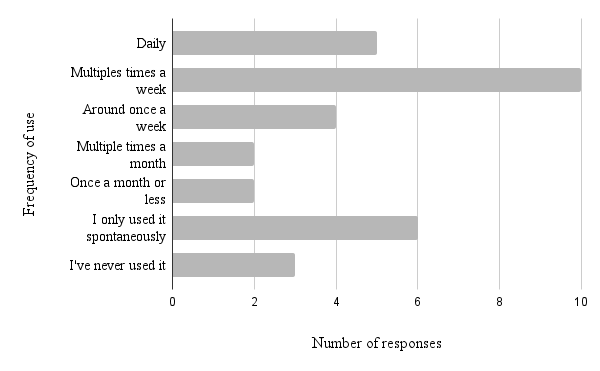

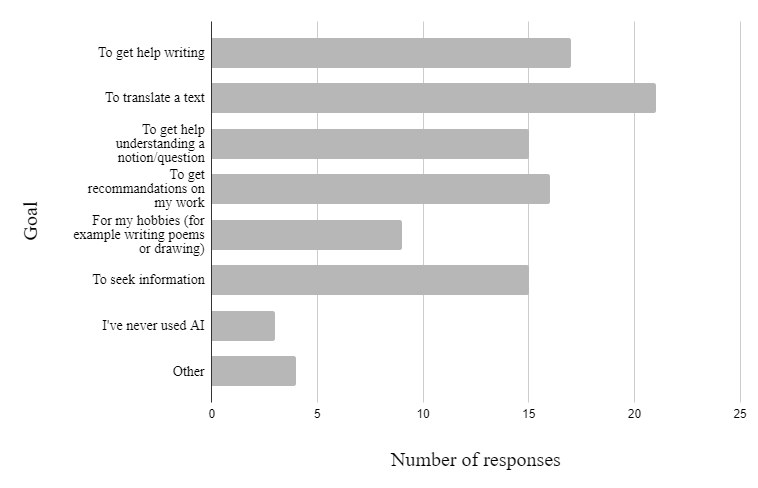

Le faible intérêt manifesté par les enseignants contraste nettement avec l’usage intensif qu’en font les étudiants. La Figure 1 présente la fréquence d’utilisation de l’IAGén par ces derniers pour leurs travaux universitaires, tandis que la Figure 2 illustre les principaux objectifs poursuivis. Comme le montre la Figure 1, près des deux tiers des étudiants déclarent une utilisation fréquente, à savoir quotidienne ou plusieurs fois par semaine. L’usage déclaré concerne principalement l’assistance à différentes étapes du travail rédactionnel (Figure 2).

Figure 1. La fréquence d’utilisation de l’IAGén par les étudiants pour des travaux universitaires (n = 32)

Figure 2. Les objectifs d’utilisation de l’IAGén par les étudiants (n = 32)

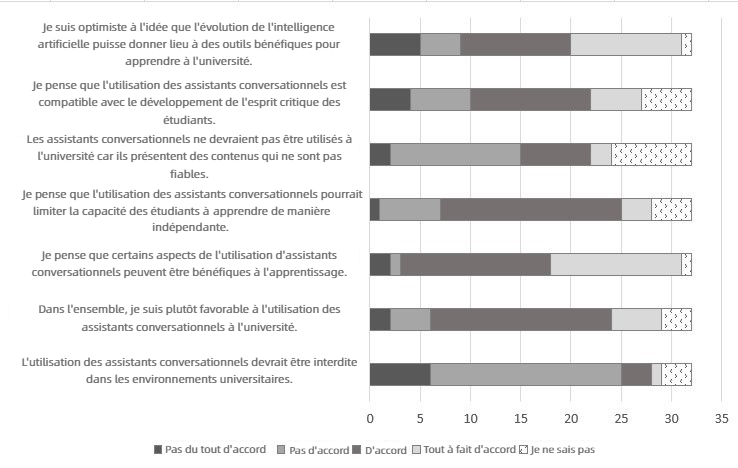

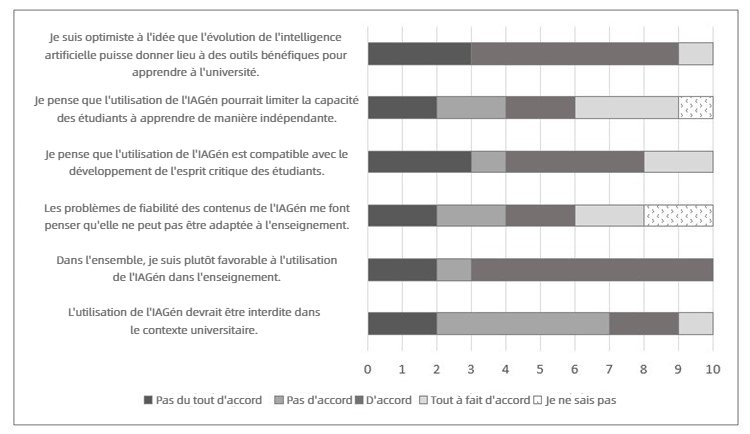

Les fréquences d’utilisation déclarées par les étudiants se reflètent également dans leurs perceptions et attitudes vis-à-vis de l’IAGén, dans l’ensemble assez positives. Les Figures 3 et 4 montrent respectivement les opinions des étudiants et des enseignants concernant l’usage de l’IAGén dans l’enseignement supérieur, mesurées à l’aide d’une échelle de Likert allant de « pas du tout d’accord » à « tout à fait d’accord », avec la possibilité de répondre « je ne sais pas ».

Comme le montre la Figure 3, une large majorité d’étudiants reconnaissent que les assistants conversationnels peuvent être bénéfiques à l’apprentissage et rejettent l’idée de leur interdiction dans les contextes universitaires. Cependant, certaines inquiétudes persistent : deux tiers des étudiants estiment que ces outils peuvent limiter leur capacité à apprendre de manière autonome et un tiers considère qu’ils sont incompatibles avec le développement de la pensée critique. Des réserves concernant la fiabilité des contenus générés ont également été exprimées, menant certains à estimer que ces outils ne devraient pas être utilisés (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Les opinions des étudiants concernant l’utilisation de l’IAGén à l’université (n = 32)

De manière similaire, la Figure 4 montre que la majorité des enseignants se déclarent favorables à l’utilisation de l’IAGén dans l’enseignement et considèrent qu’elle peut être compatible avec le développement de la pensée critique chez les étudiants. Leurs opinions concernant les limites potentielles de l’IAGén sont toutefois plus nuancées et plus également réparties. Comparativement aux étudiants, les enseignants adoptent une posture plus prudente à l’égard de ces outils et se prononcent plus fréquemment en faveur d’une interdiction à l’université. Les réponses recueillies tendent à se situer davantage aux extrémités de l’échelle de Likert, ce qui suggère des positions polarisées au sein du corps enseignant, un phénomène cohérent avec leur usage moins fréquent de ces technologies.

Figure 4. Les opinions des enseignants concernant l’utilisation de l’IAGén à l’université (n = 10)

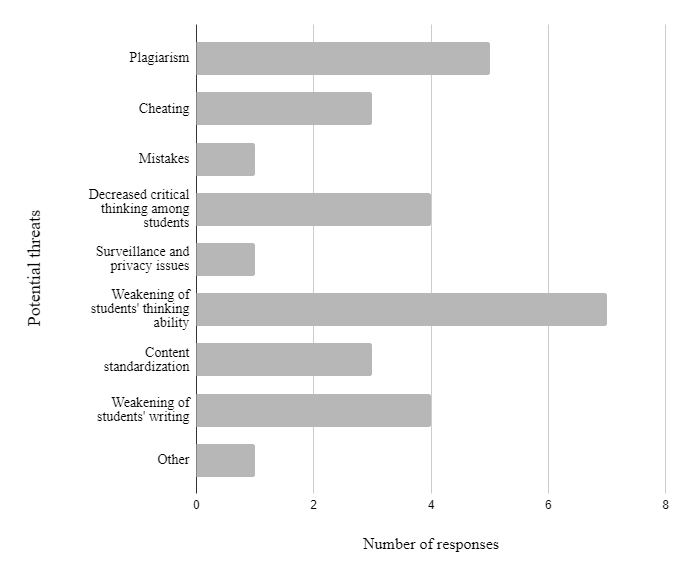

Concernant les risques associés à l’IAGén dans l’enseignement supérieur, les enseignants étaient invités à sélectionner trois risques qu’ils considéraient majeurs parmi une liste de huit. Les inquiétudes les plus souvent citées incluent l’affaiblissement des capacités de pensée critique des étudiants, ainsi que l’influence négative sur leurs compétences rédactionnelles. Le plagiat figure également parmi les préoccupations les plus fréquemment exprimées (voir Figure 5).

Figure 5. Les perceptions des enseignants concernant les risques de l’IAGén pour l’éducation supérieure (n = 10)

Discussion

Dans l’ensemble, cette étude met en évidence une perception majoritairement positive de l’IAGén chez les participants, ainsi qu’une absence de rejet marqué de son usage. Cependant, ces résultats contrastent avec les entretiens menés auprès des tuteurs, qui rapportent que de nombreux étudiants se montrent réticents à utiliser l’IAGén durant les séances de tutorat, les refus étant fréquents. Cette divergence entre les témoignages des tuteurs et les réponses aux questionnaires suggère que les étudiants les plus méfiants à l’égard de l’IAGén n’ont peut-être pas pris part à l’étude. Pour pallier ce biais, nous avons croisé les résultats quantitatifs et qualitatifs afin de mieux comprendre les raisons de ces refus. Cette approche nous permet d’identifier les attitudes récurrentes vis-à-vis de l’IAGén et d’élaborer des stratégies à destination des Writing Centers pour atténuer les perceptions négatives.

Parmi ces préoccupations, celle du plagiat apparaît comme centrale. Elle est fortement mise en avant par les enseignants dans les questionnaires et évoquée par les tuteurs comme la principale raison pour laquelle les étudiants refusent d’utiliser l’IAGén en séance. Cette inquiétude semble liée à l’incertitude quant à la manière d’intégrer les productions de l’IAGén à un travail universitaire sans franchir les limites de l’intégrité éthique. Une telle prudence est compréhensible, au vu des conséquences que peut entraîner le plagiat ; elle révèle cependant que certains étudiants ne conçoivent l’usage de l’IAGén qu’à travers la production automatisée de contenus à intégrer tels quels à leurs devoirs. Nous considérons que cette manière d’utiliser l’IAGén — en délégant la tâche à l’outil — ne constitue pas une bonne pratique. D’une part, elle repose sur la réutilisation potentielle de contenus issus d’autres sources et, d’autre part, elle ne favorise pas les processus d’apprentissage. C’est pourquoi le Writing Center cherche à promouvoir un usage de l’IAGén qui évite le plagiat et ne se substitue pas à l’effort rédactionnel des étudiants.

Les tuteurs ont également souligné que la réticence des étudiants est souvent alimentée par une méconnaissance de l’IAGén, ainsi que par les interdictions fréquentes émanant de leurs enseignants, généralement motivées par les risques de plagiat. Malgré les explications données par les tuteurs — précisant que l’usage de l’IAGén ne conduit pas automatiquement au plagiat ou à la tricherie — les étudiants refusaient fréquemment d’y recourir pour ces raisons. La littérature montre que le manque de connaissances et de confiance envers une technologie favorise son évitement (Galindo-Domínguez et al., 2024 ; Ismatullaev et Kim, 2024). Cette situation crée un dilemme pour les tuteurs, qui doivent proposer l’usage de l’IAGén tout en respectant la zone de confort des étudiants. Il leur arrivait ainsi d’éviter d’aborder l’outil lorsqu’ils anticipaient une réaction négative. Les deux tuteurs interrogés ont d’ailleurs affirmé ressentir un certain malaise lorsqu’ils proposaient l’utilisation de l’IAGén en séance, un inconfort nourri à la fois par la fréquence des réactions négatives des étudiants et par leurs propres doutes initiaux à l’égard de l’outil. Cette tension nuit à la relation tuteur-étudiant et complique l’analyse de l’impact potentiel de l’IAGén sur les apprentissages.

Une solution à court terme pourrait consister à introduire l’IAGén de manière différente dans les séances. Plutôt que de simplement en suggérer l’usage, les tuteurs pourraient, par exemple, l’utiliser directement pour générer un texte volontairement imparfait, puis inviter les étudiants à en repérer et corriger les défauts. Cette approche permet d’éviter le risque de plagiat, tout en favorisant l’engagement des étudiants à travers un défi concret, susceptible de stimuler leur implication et leur motivation (Hamari et al., 2016 ; Khan et al., 2017).

Dans les résultats de l’enquête, les enseignants ont également exprimé leur inquiétude quant à un affaiblissement des compétences de pensée critique chez les étudiants. Cette préoccupation récurrente souligne la nécessité de promouvoir un usage réfléchi et critique de l’IAGén, en cohérence avec les objectifs pédagogiques. L’approche adoptée au Writing Center vise précisément à accompagner les étudiants dans une utilisation encadrée de l’outil, en tant que soutien au processus d’apprentissage, et non comme substitut. Par exemple, lorsqu’un étudiant rencontre une difficulté récurrente en rédaction, le tuteur peut utiliser l’IAGén pour générer un texte contenant des erreurs similaires, puis guider l’étudiant dans leur identification et leur correction. Dans cette perspective, l’IAGén devient une source illimitée d’exemples à analyser, permettant de développer des compétences spécifiques. Nous pensons qu’il est essentiel pour les usagers potentiels de comprendre que l’IAGén n’a pas vocation à se substituer à eux, et qu’elle peut s’avérer bénéfique lorsqu’elle est mobilisée de manière critique et inventive.

La fiabilité des contenus générés par l’IAGén constitue également une source importante de réticence, en particulier chez les enseignants. Cette problématique revient fréquemment comme motif de rejet ou de méfiance. Neuf étudiants sur trente-deux interrogés estiment, eux aussi, que les assistants conversationnels ne devraient pas être utilisés en raison de ce manque de fiabilité. La crainte de produire des informations incorrectes ou trompeuses représente un frein notable à l’adoption de l’IAGén dans l’enseignement supérieur (Peters et Visser, 2023). Pour pallier ce risque, le Writing Center cherche à encourager un usage critique et éclairé de l’IAGén, en développant la capacité des étudiants à évaluer la fiabilité des contenus générés. En expliquant clairement que les modèles de langage peuvent produire des erreurs ou des approximations, nous incitons les étudiants à adopter une posture réflexive face à cet outil. Cette approche contribue à limiter les risques de désinformation et à positionner l’IAGén comme un outil complémentaire, et non une source d’autorité.

La différence la plus marquée entre étudiants et enseignants observée dans notre étude concerne la fréquence d’utilisation de l’IAGén. Les étudiants y recourent bien plus régulièrement, et pour une diversité de tâches (Schiel et Bobek, 2023). Cette pratique soutenue favorise la découverte des potentialités de l’outil et renforce la confiance dans son utilisation. À l’inverse, une utilisation plus occasionnelle limite la perception de ses bénéfices. Ce décalage engendre des différences de compétences et de familiarité avec l’IAGén, contribuant à creuser l’écart d’adoption entre les deux groupes et influençant leurs opinions quant à son intégration dans le monde universitaire. Les enseignants ayant participé à notre étude ont exprimé un intérêt notable pour l’IAGén, tout en se déclarant peu compétents dans son utilisation, une tendance également observée par Galindo-Domínguez et al. (2024). Cela suggère que les perceptions négatives ne découlent pas d’un manque d’intérêt, mais plutôt d’un déficit de compétences et de connaissances. De la même manière, un tuteur initialement sceptique à l’égard de l’IAGén a progressivement gagné en assurance dans sa manière de l’intégrer aux séances, à mesure qu’il en découvrait le fonctionnement et les bénéfices.

Ces observations soulignent l’importance de l’usage effectif dans le développement d’une intention d’utilisation. Or, l’évitement de l’IAGén est encore souvent conseillé par les enseignants dans leurs cours, ce qui influence fortement l’attitude des étudiants en renforçant leur réticence. Dans ce contexte, le rôle des tuteurs devient d’autant plus crucial : en accompagnant les étudiants dans un usage réfléchi de l’IAGén, ils peuvent contribuer à en améliorer la perception et l’efficacité dans le cadre des apprentissages.

Conclusion

Cette étude met en lumière la diversité des attitudes vis-à-vis de l’IAGén chez les étudiants et les enseignants du Graduate School Writing Center de l’Université Clermont Auvergne. Bien qu’une reconnaissance générale des bénéfices potentiels de l’IAGén se dégage et qu’un rejet catégorique reste rare, plusieurs préoccupations subsistent, notamment celles liées au plagiat, à la fiabilité des contenus générés et à l’impact sur la pensée critique. Ces résultats corroborent les tendances identifiées dans d’autres travaux portant sur les attitudes envers l’IAGén dans l’enseignement supérieur (Al Darayseh, 2023 ; Ma, 2023).

Nous avons observé des différences marquées entre les deux groupes, tant sur le plan des usages que des perceptions : les étudiants recourent plus fréquemment à l’IAGén et se montrent globalement moins d’inquiets à son égard. À l’inverse, un usage plus limité, un sentiment d’incompétence et une connaissance réduite semblent contribuer aux réticences exprimées par les enseignants et, par conséquent, par les étudiants lors des séances de tutorat. Les témoignages recueillis auprès des tuteurs indiquent que ces attitudes influencent également leur propre confiance à introduire l’IAGén au cours des séances.

Cette étude présente certaines limites, notamment un faible taux de réponse et un biais potentiel de participation, les personnes les plus réfractaires à l’IAGén ayant probablement choisi de ne pas répondre au questionnaire. Pour pallier cette limite, nous avons complété les données d’enquête par des entretiens semi-directifs avec les tuteurs, afin d’éclairer plus finement les perceptions des enseignants et des étudiants. Nous estimons que les Writing Centers peuvent jouer un rôle central dans l’atténuation des inquiétudes liées à l’IAGén, en en promouvant un usage cadré et pédagogique : un usage qui stimule la pensée critique, évite le plagiat, valorise ses apports potentiels et rassure quant aux risques réels. À partir de ces constats, nous adapterons les futures séances de tutorat pour mieux prendre en compte ces perceptions, et ainsi créer les conditions d’une exploration plus approfondie de l’impact réel de l’IAGén sur l’apprentissage de l’écriture universitaire.